11/05/2020

As a relative newcomer to the world of institutional investing, I was struck by the volume of phrases and acronyms used to define several aspects within the industry, not least with regards to responsible investing.

However, when I first came across the phrase ‘impact investing’, I thought this would be a term that would be one of the easiest to understand, given it does exactly what it says on the tin. Making an impact through investing.

It is defined by the Global Impact Investing Network as “investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” The purpose of this type of investing, and indeed its advantages, are clear; achieving positive returns (of some level) on investments while also generating positive social and environmental benefits and outcomes.

But according to Research in Finance’s inaugural UK Responsible Investing Study (UKRIS) conducted at the start of 2020, impact investing is not yet mainstream across the institutional investment space. A lack of understanding is precipitating a low proportion of consultants and schemes stating their recommendation or use of impact investment strategies.

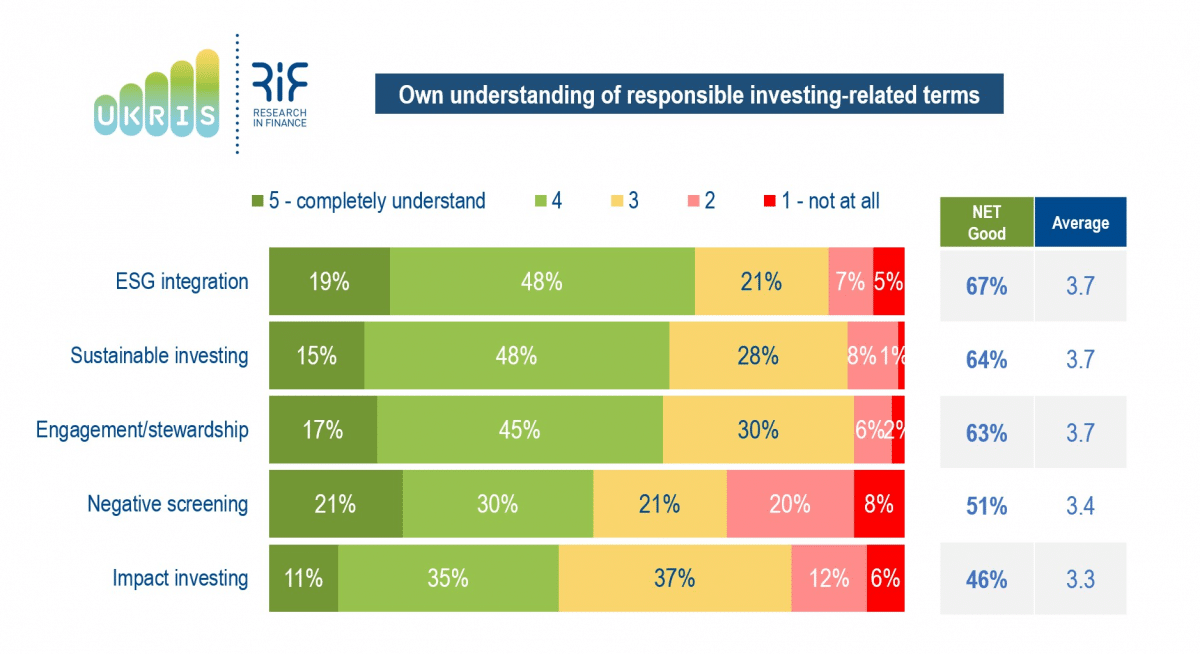

‘Impact investing’ is the least well understood phrase across the responsible investing terms asked about in UKRIS, with only 11% of consultants and schemes stating that they completely understand what it means. When splitting out by job role, scheme managers and trustees are less sure compared to consultants and professional trustees.

And while most cite that their pension fund / the pension funds they advise invest in responsible funds of some kind, only a fraction invest in funds/strategies with an impact investment focus, with stated use lower than stated use of ESG integration funds, sustainability-focused funds and funds with a negative screening applied.

When asked about who the perceived market leaders are for impact funds, consultants lean towards LGIM, the largest manager for pensions in the UK, and Impax, an impact specialist, whilst schemes cite AXA IM and Ninety One (formerly Investec AM) as leaders. However, the proportion mentioning any of these investment managers does not exceed 25% share, highlighting the lack of a clear front-runner for impact investing.

Given both current use and knowledge may be low, it is even more important to understand what the future demand for impact investing is, and what might be inhibiting uptake. Results from UKRIS detail that future demand, like current use, is relatively limited. This lack of appetite is a significant challenge to the future of the investment management industry but can be addressed by attempting to decipher how impact investing is defined and what it truly encompasses in the real world of investment.

To do that, it is imperative to understand what a “measurable social and environmental impact” looks like as a tangible outcome. Investing in a certain infrastructure project that aims to develop a type of public building in a community, such as a leisure centre, is an example to consider. The building may benefit many local residents with regards to improved physical and mental health as well as the creation of new jobs, and if green technology is used as part of the building process, this will keep carbon emissions as low as possible. These outcomes will no doubt generate positive externalities, both socially and environmentally.

Measuring these externalities is where the complexity lies. How low do the carbon emissions need to be to be classified as purposeful impact investing, and how many people need to use the building in a certain timeframe for the social benefits to meet the impact investing benchmark?

Difficulties of measurement against industry-recognised standards is something which is not limited to impact investing; it is a problem which can be found under the entire environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing umbrella. Lack of standardisation is a barrier and limitation that threatens the promotion of responsible investing more widely.

New regulation is attempting to address this issue, such as the consultation process launched by the European Supervisory Authorities with respect to “the content, methodology and presentation of ESG disclosures”. This means that investment managers may have to spell out the adverse E and S impacts of their investments on their website from next year if this regulation passes. Conversation and improved information around the promotion of ESG characteristics and how to standardise this regulation on an industry-wide scale, will help with both clarity and transparency of how to define elements such as “green economic activity”. This in turn, will ideally lead to better understanding and therefore impact investing becoming more popular.

Indeed, I do not think it is such a leap to suggest that as information and regulation improves and the waters around responsible investing become less muddy, impact investing should be considered the gold standard, as opposed to simply more popular. Impact investing is characterised by positive externalities with the introduction of social and environmental benefits. This ripple effect should be championed within the industry, as investing that results in a stronger, more resilient financial system, can then allow further investing, as well as the potential likelihood of stronger returns.

If all personnel in the institutional investment world can collaborate and engage by positioning measurability as the goal for any ESG regulation, then this can only make impact investing more transparent, more accessible, and therefore more mainstream. Institutional investors have the funds and influence to make a difference, as well as the investment time horizons to support largescale projects with positive E and S impact. But as our research from UKRIS indicates, there is certainly a long road ahead to the three-step process of improving understanding, increasing use and then driving demand.

For the institutional component of our UK Responsible Investing Study, we surveyed 155 investors and advisers, including consultants, scheme managers, pension fund CIOs, trustees and professional trustees. The study provides detail on perceived market leaders across a range of different RI funds/strategies, crucial insight into how professional investors and their advisers assess these products, and steers on how to differentiate in an increasingly busy marketplace. If you would like to know more about this influential study and what is on offer, please contact Richard Ley or Toby Finden-Crofts.